Background

The

basics: Flex Mentallo is a miniseries by Grant Morrison

and Frank Quitely, published by DC Comics/Vertigo from June-Sept. of 1996.

The two major characters of the work, Flex Mentallo and Wallace Sage,

had initially appeared in 1991, in the pages of Morrison and Richard Case's

Doom Patrol (although the Wallace Sage that initially appeared

differs significantly from both the Wally that appears in the Flex

comic book and the Wally that is described in Flex Mentallo's

text pages).

The

basics: Flex Mentallo is a miniseries by Grant Morrison

and Frank Quitely, published by DC Comics/Vertigo from June-Sept. of 1996.

The two major characters of the work, Flex Mentallo and Wallace Sage,

had initially appeared in 1991, in the pages of Morrison and Richard Case's

Doom Patrol (although the Wallace Sage that initially appeared

differs significantly from both the Wally that appears in the Flex

comic book and the Wally that is described in Flex Mentallo's

text pages).

Flex Mentallo is not merely Grant Morrison's creation, however: he is also a reiteration of the 20th-century mass-market Hercules, Charles Atlas. Charles Atlas plays an important role in superhero comic books, the final step in identification; while superhero comics narrate physicality and power in the form of the hero, Charles Atlas packages this power into a commodity that the reader can, presumably, access and utilize.

In Doom Patrol the "Secret Origin of Flex Mentallo" is a pastiche, a direct homage to the Charles Atlas "myth" (it is, at many points, nearly identical to "The Insult that Made a Man out of 'Mac'") which is seasoned with the surrealist flavor that came to characterize Doom Patrol. Flex is "Mac" made superhuman; he is then, indirectly, an emblem of the reader's investment in and identification with the superhero comic.

Atlas represents two ideas, seemingly conflicting, that are major themes in Flex: a) that superhero comic books are essentially product, debris, inseparable from their presence as stuff; they are consumed and then left as a constant reminder of "junk culture"; b) that superhero comic books are potentially transformative, that they engage in a multilayered system of representation and crossover that, in the end, implicates even the reader.

|

|

Flex Mentallo is also a reaction to an "age" of comics that was at its end when the series was published, the "Dark Age". This "Dark Age," generally located in the '80's and early '90's, contained a couple of happenings that are rather relevant to Flex--the "grim and gritty" trend in characterization and the transformative DC mini-series Crisis on Infinite Earths.

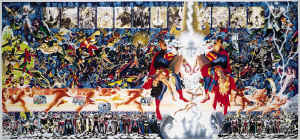

The superhero comic book as a medium is extremely conscious of its own history; as an ongoing serial narrative with a devoted--often, arguably, obsessive--readership, the superhero comic can engage in a level of metatextual play that a less doggedly followed medium might not be able to successfully maintain. In superhero comic books, revisions of superheroes traverse time and space to engage in dialogue with their previous iterations; in Crisis on Infinite Earths, partially depicted in the image above, Supermen of two worlds and ages (the original Superman, who debuted in 1938, and the "current" Superman) share grief as the "multiverse" in which they live faces apocalypse. Time, space and representation are played with using the vehicles of sci-fi physics and superhuman power; the true super-power is, often, an ability to defy conventional or linear textuality.

The Crisis on Infinite Earths, published in 1986, went a long way in closing down much of that multivocality that had come to characterize the "DC Universe," a corporate narrative that involved 50 years' worth of superheroes and their stories. In this "reboot" or large-scale revision, the multiple iterations of superheroes were eliminated: where there were dual or multiple Supermen previously, Crisis established one Superman, one Wonder Woman, one of each superhero figure as "true." Crisis brought canonicity to the "universe," and therefore shut down the trope of crossover which is so powerful a facet of superhero comics as a medium. The Crisis is refigured in Flex #4 as the Legion of Legions' climactic battle with "The Absolute."

While Crisis on Infinite Earths diminished the multivocality of DC Comics, other texts were complicating the superhero as a character type; "graphic novels" like Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns reconceived the superhero as an often tortured, morally ambiguous and sometimes violent figure. Characters like Marvel's Punisher and Wolverine became popular as readers responded to a more flawed, brooding, anti-heroic (Byronic?) sort of character.

Flex the character and Flex Mentallo the series display Morrison's protest against these trends in superhero comics as an ongoing medium. Flex is hyperbolically superheroic, almost a caricature: he "fights crime with a smile" and enjoys milk at the local bar. However, other characters in Flex Mentallo, after overcoming their initial skepticism, often react to this attitude with deference, respect, gratitude--they seem refreshed by it. Flex absorbs the obvious critique he provokes and moves his "readers" beyond it; he represents Morrison's argument for a space beyond critique. Even as Flex the character promotes a revised approach to the superhero, Flex Mentallo presents a new multivocality as a superhero comic book; crossover and play are brought to the fore as numerous levels of representation, of "textuality," are juggled and blended in a celebration of multilinear narrative.

This annotation copyright © 1999-2000 Jason Craft. Flex Mentallo and all images are copyright © 1996 DC Comics/Vertigo.